This is historically confusing, however, since the scene takes place not in the mid-1940s, when they wrote Hippos together, but in autumn 1953 in Ginsberg’s lower East Side apartment. Our next scene is prompted by the image of Burroughs besting Kerouac in a fight, which appears on the jacket of the U.S. In practice, the extent of the collaboration here - writing alternate chapters - is pretty limited but, as a principle, it’s a significant opening up of the author’s presumed autonomy, the singularly private and solitary act of writing. The point is not that we have to choose between these extremes of reverence and cynicism just that we should recognise both are possible.Īnd second, Hippos is an important instance of authorial collaboration - important because rare in its own right and because it occurs right at the start of these two writers’ literary careers. If we look through the other end, however, it’s a minor bit of undistinguished juvenilia that’s only seeing the light of day at all as a cash cow for the Burroughs and Kerouac estates, keen to exploit the endlessly recycled narrative of Beat mythmaking and hagiography. But I want to make two points of a different kind.įirst, if we look through one end of the telescope, Hippos is a fascinating primary document, a major foundational text for the Beat movement and the record of a crucial event in the formation of the Beat circle - well worth the wait.

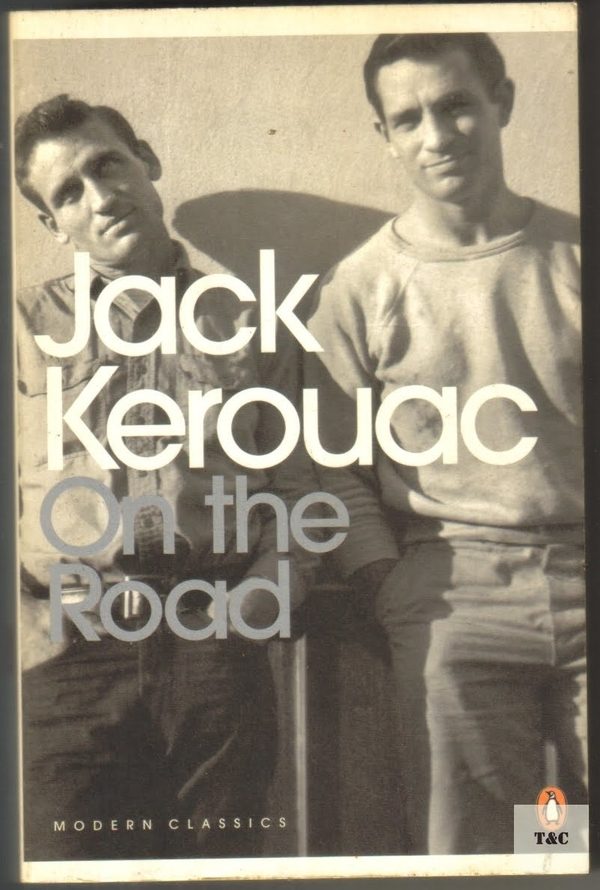

Of course, there’s more to it than that - even just in terms of stylistic debts, since I would suggest that the prose rhythm is also informed by a modernist tradition that includes Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler’s The Young and Evil and Joseph March Moncur’s The Wild Party. Here we see them acting out in the grounds of Columbia University a scene from Dashiell Hammett, which confirms both their taste for self-dramatisation and the hardboiled detective style in which they wrote about those boiling hippos.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)